However, the image of 2019 that highlights the disconnect between our cultural and visual framing of the outdoors, as well as our terrifying impacts and consumption of it, was taken at supposedly one of the most difficult places to reach on the planet.

Almost 66 years to the day from when Mount Everest was first climbed, Nepalese mountaineer Nirmal Purja photographed 100 people queuing to reach the summit. 2019 is now considered to have been one of the deadliest climbing seasons on Everest. While the good weather window that year was short, the problem wasn’t blizzards or avalanches, but too many people on the mountain. Veteran climbers and industry leaders have blamed these deaths on overpopulation, with particular focus on too many inexperienced climbers. (9) The above image sent shockwaves around the world as those who knew “nothing about mountaineering were shocked by this contradiction between the mountain’s reputation as a lonely and unattainable peak, and the banal reality of a rush-hour crush.” (10) That year saw a record number of permits to climb the mountain issued by the Nepalese government, and after the climbing season closed there were no signs that numbers would be restricted in the following year. As our consumption of nature felt like it was spiraling out of control, the world was brought to a standstill by the global Covid-19 pandemic.

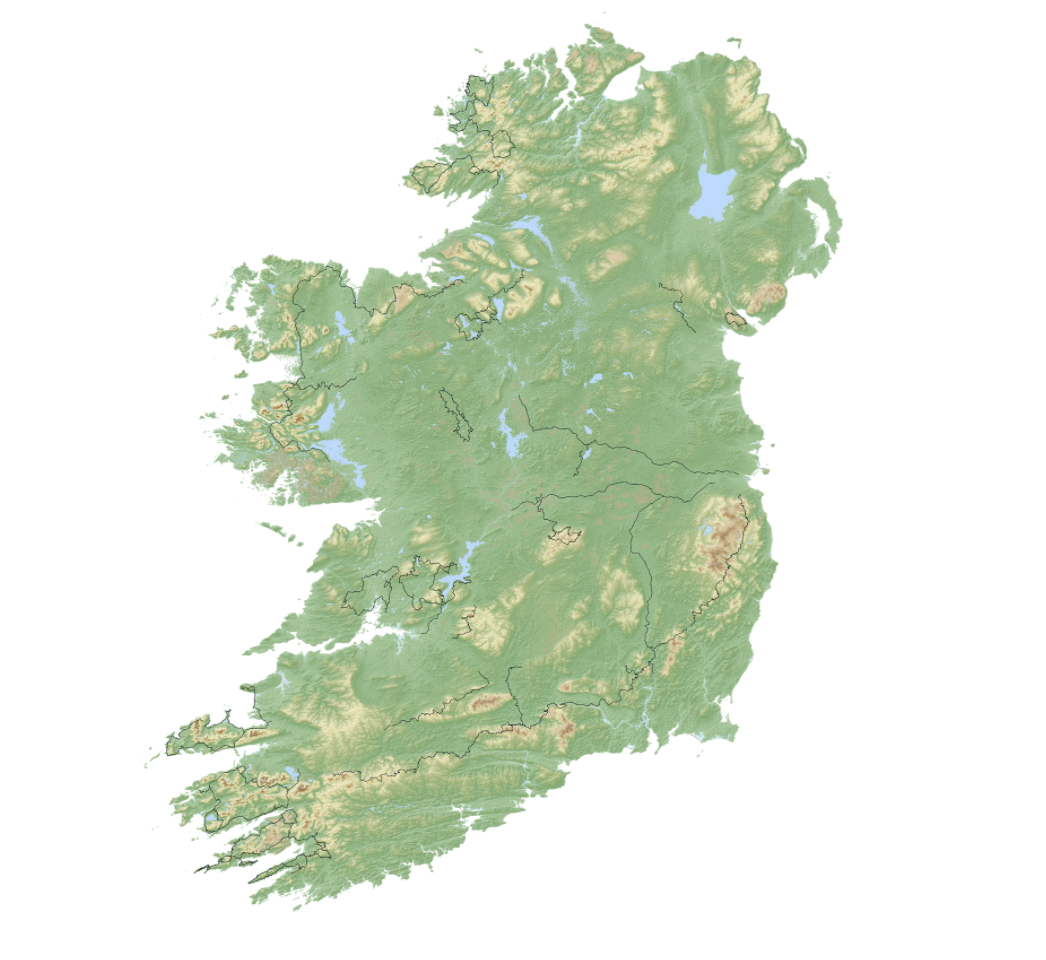

When I started my research into walking I never expected a stage where I wouldn’t be able to go further than a couple of kilometers beyond my house. At the time of writing, March 2021, the world is one year into the Covid-19 global pandemic. In the past year Ireland has gone through a number of ‘lockdowns’, with movement restricted to specific distances from place of residence, or within regional counties. However, during these months there has been a marked increase in people ‘finding’ the outdoors. Mountaineering Ireland, (11) the recognised National Governing Body for mountaineering, hillwalking, rambling, and climbing, published an article by Helen Lawless in the Summer 2020 edition of The Irish Mountain Log, titled ‘Increase in physical activity seen during time of Covid-19 restrictions’. In the article Lawless writes how although many people cannot partake in their usual activities during Covid-19 restrictions, “research has shown that many people have ‘found’ the outdoors at this time.” (12) This research, conducted by Ipsos MRBI on behalf of Sport Ireland, (13) reports that “Irish adults walking at least once a week for recreation has increased throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, reaching 83% in May” 2020, and that “the percentage of people that are inactive is at its lowest ever (11%).” (14) In her article, Lawless questions how this new level of participation can be sustained into the future, with no clear answer in sight.

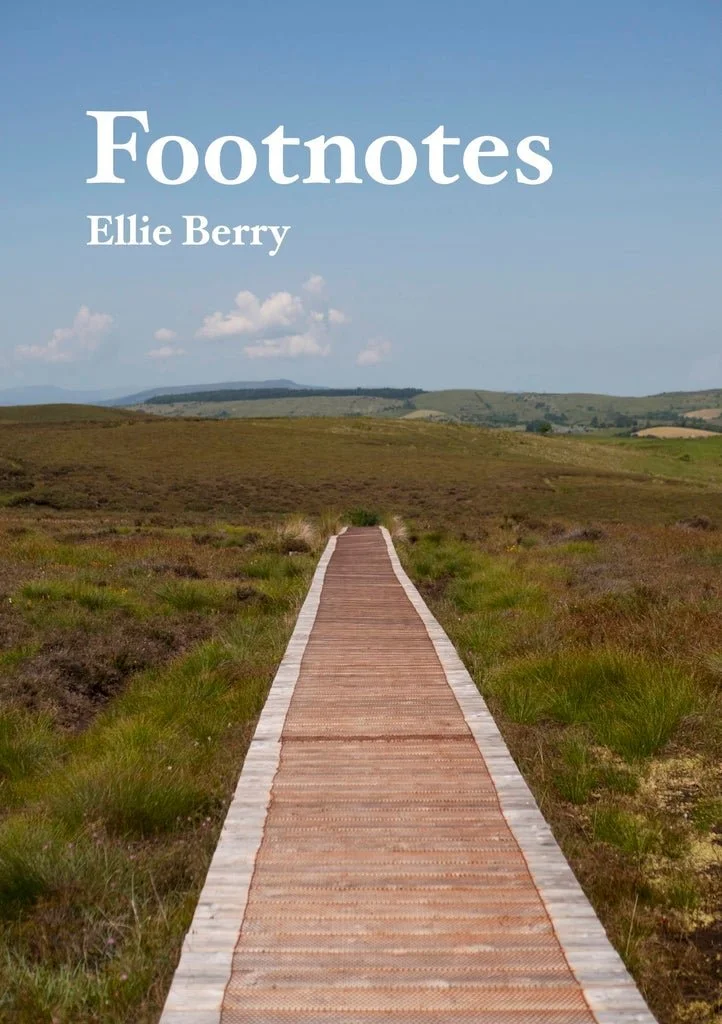

As the Access & Conservation Officer for Mountaineering Ireland, Helen Lawless has written about the impact of our increased recreational use of the outdoors in previous editions of The Irish Mountain Log. In Issue 132 (Winter 2019) Lawless published the article “Learning from Cuilcagh,” (15) a follow-on from a piece she wrote in 2017 about the same area, titled “Much to be Learned From Experience at Cuilcagh”. (16) Based on the titles I immediately knew that these articles would provide insight into the under researched topic of the cause and effect of an Irish location becoming famous on Instagram - I have seen this place hundreds of times depicted on the social media platform. Online this hike is known as ‘the stairway to heaven’, as the route follows a long boardwalk and staircase up to the summit of Cuilcagh Mountain (665m), the highest point in counties Cavan and Fermanagh. The focal point of all of the images that I have seen of the trail and surrounding area focus on the structure of the boardwalk, as the sun-bleached wood stands out starkly from the blanket bog landscape it twists through.

In the first article in 2017, Helen Lawless describes the background to the area: in the late 1990s all commercial peat farming ceased, and the bogland went through a series of conservation processes as a classified Special Area of Conservation (SAC) through the EU LIFE programme. Between 2003 and 2008 two walking trails were routed across this area, which encouraged more footfall and caused the trampling of a wide area as walkers tried to follow the trail without walking through other trampled, boggy areas. Early attempts at rectifying this problem only exacerbated the trampling of flora and destruction of the fragile ground, leading to a brief closure of the affected area. The council overseeing the development of the area decided to build a boardwalk (in this instance, boardwalk meaning a raised wooden walkway with handrails) to protect the area from further erosion.

In her article, Lawless writes that the announcement to build a boardwalk up to the summit of Cuilcagh mountain was met with concern from members of Mountaineering Ireland, who wrote to the Geopark that the bogland was part of, highlighting their issues. These issues included concern for “the visual impact of the boardwalk on the landscape, that the structure was out of proportion to the modest degree of erosion on Cuilcagh and that, through increased usage, it could exacerbate impacts on the summit plateau.” These concerns were, according to Lawless, ignored, as the legal category of the land didn’t require any further environmental assessment. At the end of this paragraph Lawless reiterates how “landscape and visual impact were not considered.”

The title of the next section of her article, The impact of social media, pinpoints just how far our lexicon and cultural landscape has changed in the past ten years. Lawless writes that in 2017, a video of this boardwalk became famous, “reaching 1.4 million views in three weeks,” which resulted in an estimated 3,500 people visiting Cuilcagh over the four day period of the Easter weekend that year, “greater than the total number of visitors for all of 2013.” From here Lawless draws our attention to the impact and stress this caused to the local residents and landowners, the extra security firm brought in to manage traffic, and the overworking of the Geopark staff. Lawless conducted a site visit 5 months after Cuilcagh’s rise to fame, finding that the erosion after the end of the boardwalk spanned an area wider than 50 metres, and continued across the ridgeline of the mountain for 1 kilometre. This high volume of tourism aged the area by 10 to 20 years of footfall within the space of these first few months.