In 2016 I wrote a thesis for my BA in Photography titled:

The Poetics and the Politics of Imagery:

National Geographic's representation of place through Instagram.

I've decided to revisit my thesis as it was something I enjoyed working on at the time. Some of my opinions might have stayed the same, and on other things I've definitely changed, so it's been really interesting to share what I wrote then. First, there was the Introduction. Then there was Chapter One: the Poetics, Chapter Two: the Politics, and Chapter Three: The Imaginary. Finally, this is the conclusion.

A Conclusion

For it is true that no production of knowledge in the human sciences can ever ignore or disclaim its author’s involvement as a human subject in his own circumstances, then it must also be true that for a European or American studying the Orient there can be no disclaiming the main circumstances of his actuality: that he comes up against the Orient as a European or American first, as an individual second. And to be a European or an American in such a situation is by no means in inert fact. It meant and means being aware, however dimly, that one belongs to a power with definite interests in the Orient, and more important, that one belongs to a part of the earth with a definite history of involvement in the Orient almost since the time of Homer.[1]

After providing a small background to the beginnings of National Geographic, chapter one focused on developing ideas of representation. Starting with Saussure and observing how meaning is implied through associated idea and the existence of an opposite, I then drew on Roland Barthes’s theories of representation, specifically how representation works as a cyclical process of ideas becoming representations, which become the foundation of further representation. This is the meta-data that structures culture and forms what societies are built on. It is this structure through which people witness themselves and recreate themselves for consumption.

I use these concepts to bring Orientalism by Edward Said into the discussion. Said foregrounds his work by discussing how this constant evolution of representation has lead to today’s representation of the Orient.[2] When tourists, travellers, or explorers travel to other places, their aim is to reiterate the expected representations of those places. The chapter concludes with Yi-Fu Tuan and his work on ‘Space’ and ‘Place’. Tuan states that ‘place’ holds more power than is acknowledged; it embodies the geographical location, the people and their mindset, traditions, and culture. Once the power is realised, ‘place’ and it’s relation to time also changes. When Western society contemplates distance, thoughts of ‘near’ and ‘far’ are tied to concepts of ‘here’ and ‘there’ respectively. A distant place can suggest the idea of a distant past: when travellers and explorers go to far off lands, they appear to be moving back in time.[3]

The discussion in chapter two is split into two major themes; digital as a medium and the content analysis of National Geographic’s Instagram account.

The digital debates start off explaining the birth of digital technology in relation to photography, and the negative response it received. The discussion moves to present day, and I remark on the dematerialisation of photography and the overload of images into everyday life that has been facilitated by online media. I explain that it is from my personal experience of this constant stream of new imagery, and the fact that I have not seen a large analysis of social media imagery conducted, that I decide to apply my content analysis to one of National Geographic’s social media accounts. I then draw on Tuan once more, connecting his ideas of space and place to the transient nature of the internet. I argue that through the constant redistribution of images in online media, their time and place are lost, resulting in the viewer being able to choose where the image is from through assumed representations, and from that the time the image is supposed to function in.

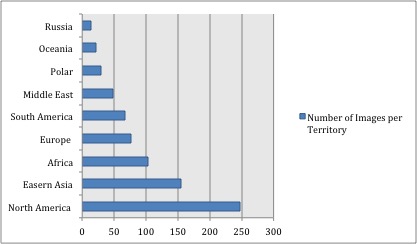

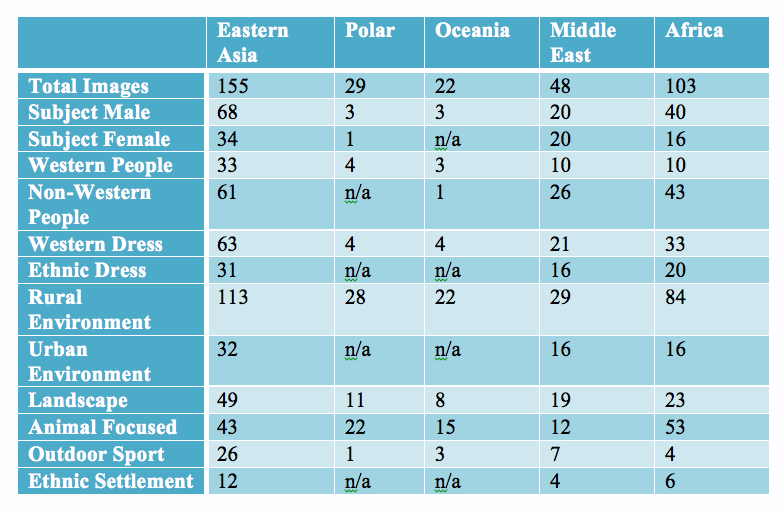

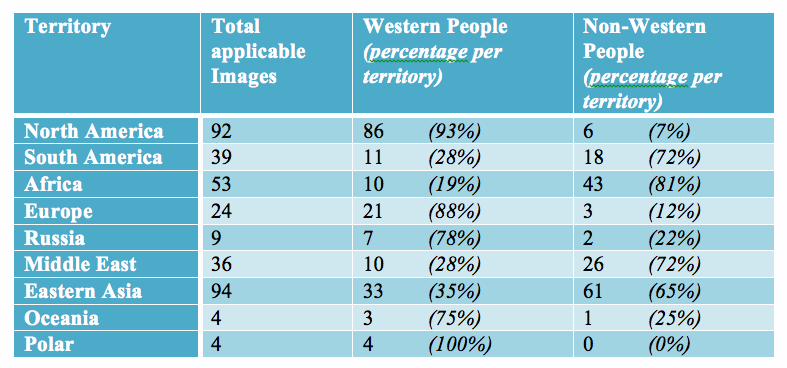

In the second half of chapter two, I analyse 782 images from the NatGeo Instagram account. Drawing on the work of both Gillian Rose, and Catherina Lutz and Jane Collins, I lay out how a content analysis is constructed and functions. When examining the results, it is clear that the representation of specific regions through recognised tropes presents ‘not just [the] topography but [the] ideology’ behind exploration imagery; ‘the camera, like the pen and the brush, when wielded by Western travellers, depicted the world in Western terms.’ [4]

A content analysis conducted on imagery is certainly an interesting way of reading trends within a large number of images, but it will never be as scientific as the idea of it claims to be. Every stage of a content analysis involves the person conducting the study to decide upon the significance or meaning of what they are evaluating. To do so without viewing the images through my own preconceived ideas would be ideal, but is impossible by the very fact that I am human.

However, because it is not a completely scientific method of analysis does not void it as a method of examining work. For this thesis I analysed a very large number of images, and have not been able to discuss as many of the results, simply as I each point can easily fill the allotted word count of this entire thesis.

Chapter three, The Imaginary, is based around Schwartz and Ryan’s piece Picturing Place, once more examining the concepts of space and place within the photographic image. This chapter deals with these themes in a more in depth analysis. Specifically looking at the westerner’s placement within images of non-Western countries, I argue that both the people and the landscape of these places have become a backdrop for the Westerner to reaffirm their identity upon. However, it is no longer through the viewing of our opposite that gives us meaning, and conformation of the power of the West. It has now become almost exclusively about the individual, the explorer, and how westerners build an images of themselves that is exciting, attractive, morally pleasing, etc. I discuss that part of the reason for this focus on the individual has evolved from creating online identity. The photograph viewed online has become the creator of identity. Through publishing socially expected and accepted images, people can now choose what part of themselves they wish to express publically.

My discussion progresses to explaining how National Geographic try and form a connection with the passing online viewer through using generic relatable subjects (the genderless refugee child), and an aversion to any imagery containing violence.

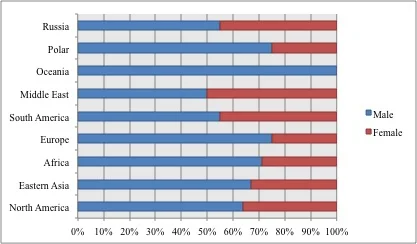

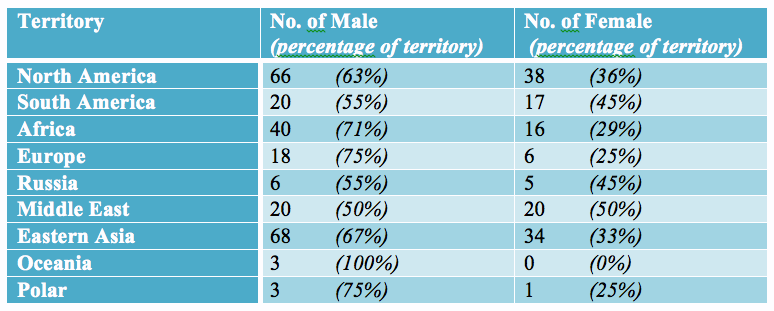

Returning to my content analysis results, I comment on the higher percentage of female representation in the Middle East and Russia territory, linking this to an emasculation of that landscape because of tense relations between the United States and those geographical areas.

I then expand on the topic of imagined geographies, moving to situations outside of the NatGeo account, drawing on the faked migrant Instagram account established as part of the international photography festival of Getxo’s publicity campaign. I state that the photography produced today remains tied to the same trap of only representing social expectations and approved aesthetics. We now consume imagery that is created to give us an instantaneous connection to a person that is easily relatable to, or we enable the spread of images containing the view of the world that we approve of and then mimic in our own hopes of being socially recognised.

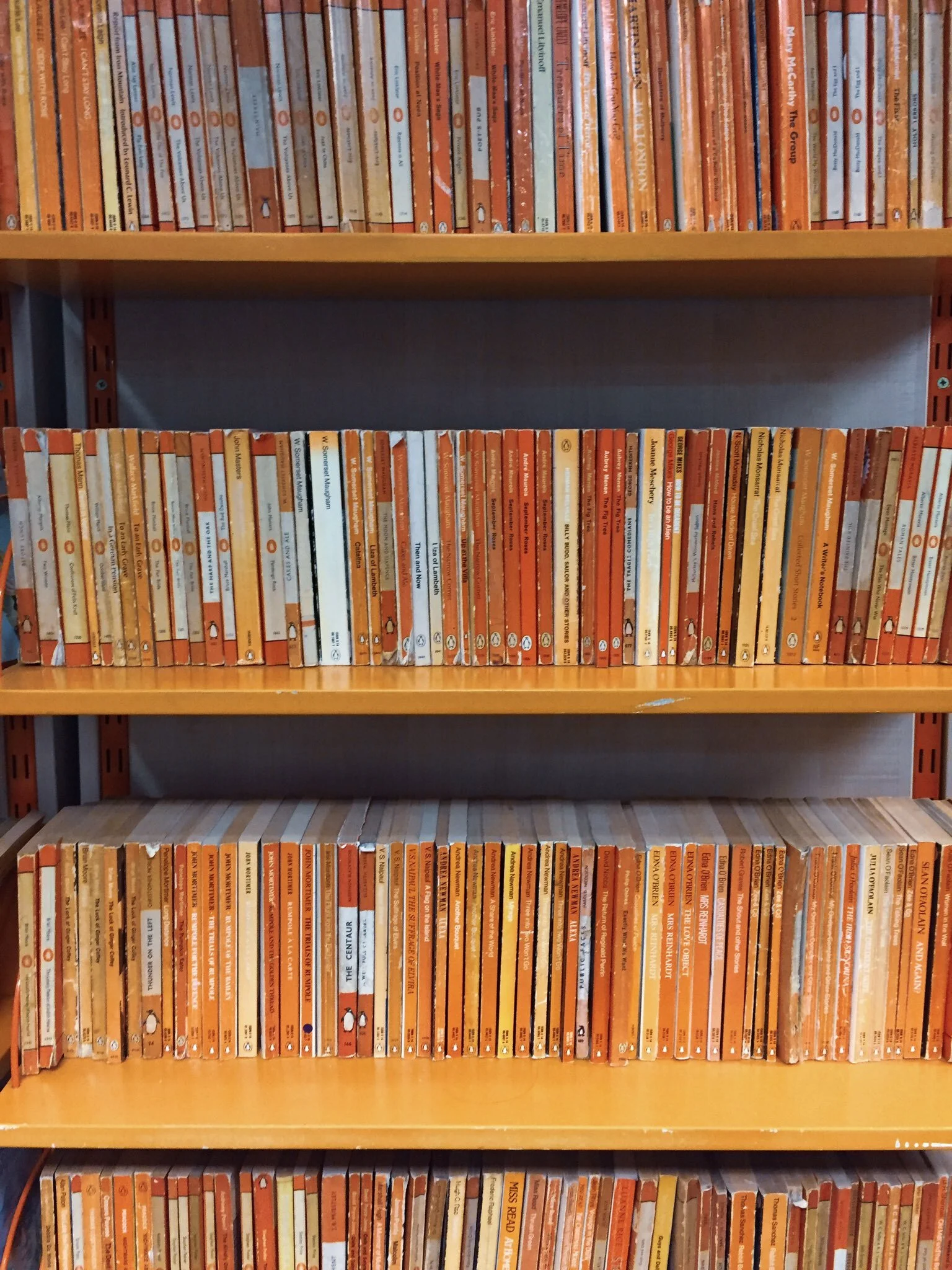

There is a certain difficulty being someone of western origin conducting an analysis on imagery of western and non-western culture. As mentioned in my introduction, one the primary reason I choose photography was seeing photographs of far off places and wanting to replicate them. I grew up looking at the highly saturated images printed in National Geographic, and continue to peruse their pages as almost a secret guilty pleasure I refuse to admit to. Drawing from the quote of Said on the first page of my introduction, I am yet another who has chosen to look at the orient as a career, and I realise that the results I have drawn from the analysed imagery are biased in their findings. Realising that many are raised to believe in the verisimilitude and almost positive scientific power of photography, there is little that can be done to change the way images are produced and consumed.

On one hand I could be generous and regard National Geographic’s work as ‘good’; they are representing areas that are normally discussed in a negative light in the western world, as places with more than those negative qualities; they are at least educating people to the fact that there is more to these places than is commonly shown. However, I think that they are committing more harm by simply creating these visually pleasing images and turning these places into serviceable backdrops for the West to parade in front of. They have built a company that profits off of ‘a distribution of geopolitical awareness into aesthetic.’[5]

In this continually growing online culture, I think that imagined geographies and the idea that a place depicting a different environment to yours is both of a far away location and a distant past, will overthrow physical geographical knowledge. Photographs of romantic landscapes will become imagery of Europe, while Africa becomes no more than one large animal sanctuary.

Appendix

Content Analysis

This content analysis used the @NatGeo Instagram account as the source for its sample pool. Each image between March 25th 2012 to October 1st 2015 was saved, along with; the caption; number of ‘likes’ that image had so far received; number of comments the image had so far received; date published; and any hash-tags used. All imagery was then saved to a host, where images were randomly generated for me to categorise. I apply the relevant categories; the host saves the applied categories, and gives me another random image to categorise. I am then able to view the frequency and distribution of categories.

Total Images Analysed: 782.

Sample Size metrics:

Population Size: 8,376

Confidence Level: 95%

Margin of Error: 3.5%

Minimum No. of Images: 717

Full Results:

(fig. 4.1) Content Analysis: full results part one.

(fig. 4.2) Content Analysis: full results part two.

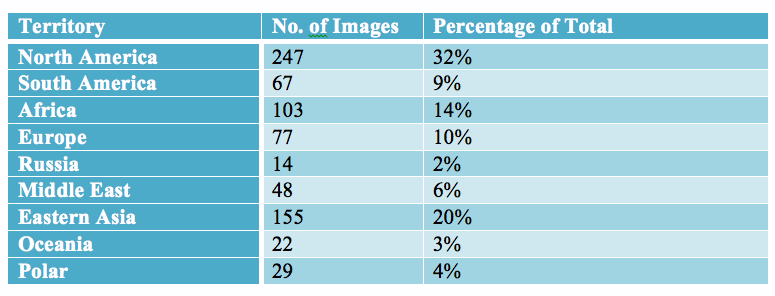

Number of Images per Territory: 762

(Fig. 4.3) Content Analysis: Images per territory.

Male Vs. Female:

Overall: 384

Male: 246 (64%)

Female: 138 (36%)

(fig. 4.4) Content Analysis: Male and female representation.

West Vs. non-West:

Overall:

West: 186 (54%)

Non-West: 160 (46%)

Per Territory:

(fig. 4.5) Content Analysis: Western and non-Western representation.

Bibliography

Barrett, Terry. Criticizing Photographs: An Introduction to Understanding Images. 3rd ed. Mountain View, CA: McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages, 9 July 1999. Print.

Bull, Stephen. Photography. 1st ed. London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2 Mar. 2009. Print.

Culler, Jonathan. Framing the Sign: Criticism and Its Institutions. Oklahoma City: Oklahoma University Press, 1989. Print.

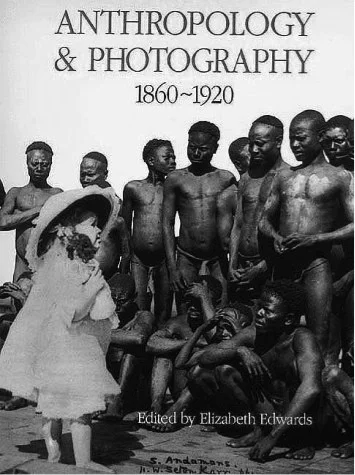

Edwards, Elizabeth, ed. Anthropology and Photography, 1860-1920. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press in association with the Royal Anthropological Institute, London, 1994. Print.

Green, Jennifer Marion. “Anthropology and Photography 1860 - 1920.” Victorian Studies 38.1 (Jan. 1994): 115–117.

Hall, Stuart. “The Work of Representation.” Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. Ed. Stuart Hall. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage in association with the Open University, 1997. 1 – 75. Print.

Lutz, Catherine A., and Jane L. Collins. Reading National Geographic. 1st ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993. Print.

Osborne, Peter D. Traveling Light: Photography, Travel and Visual Culture (The Critical Image). 1st ed. New York: Manchester University Press, 10 June 2000. Print.

Quammen, David. “Darwin’s First Clues.” National Geographic 215.2 (Feb 2009): 36 – 55. Print.

Ritchin, Fred. “Photojournalism in the Age of Computers.” The critical image: Essays on contemporary photography. Ed. Canol Squiers. London: Lawrence & Wishart, 14 Oct. 1991. 28 – 38. Print.

Rose, Gillian. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials. 1st ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2001. Print.

Ryan, James R. Photography and Exploration. United Kingdom: Reaktion Books, July 2013. Print.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient. London: Penguin Classics, 28 Aug. 2003. Print.

Schwartz, Joan, and James Ryan, eds. Picturing Place: Photography and the Geographical Imagination (international Library of Human Geography). LONDON: I. B.Tauris & Company, 19 Apr. 2003. Print.

Schwartz, Joan M. “The Geography Lesson: Photographs and the Construction of Imaginative Geographies.” Journal of Historical Geography 22.1 (1996): 16 – 45. Print.

Smith, Marc A., and Peter Kollock, eds. Communities in Cyberspace. London: Routledge, 1999. Print.

Tuan, Yi-Fu. “Space and Place: Humanistic Perspective.” Philosophy in Geography (n.d.): 387 – 427. Print.

Online Sources:

Anderssen, Erin. ‘Photo-overload: Everyone’s taking pics, but is anyone really looking?’. The Globe and Mail. [www document] <http://www.theglobeandmail.com/technology/photo-overload-everyones-taking-pics-but-is-anyone-really-looking/article4365499/?page=all>

(Date Visited: 11 Jan. 2016) (Date Last Upadated: 25 Jun. 2012).

Arthur, Charles. ‘The History of Smartphones: Timeline.’ The Guardian. [www document]

<http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2012/jan/24/smartphones-timeline>

(Date Visited: 12 Jan. 2016) (Date Last Updated: 9 Jan. 2016).

Coulehan, Erin, and Mahak Morsawala. ‘Leading the double Instagram life: When the secret “fake” account looks infinitely more real.’ Salon. [www document] <http://www.salon.com/2015/07/10/leading_the_double_instagram_life_when_the_secret_fake_account_looks_infinitely_more_real/?>

(Date Visited: 12 Jan. 2016) (Date Last Updated: 10 July 2015).

Geographic, National. ‘About the national geographic society.’ National Geographic Society Press Room. [www document]

<http://press.nationalgeographic.com/about-national-geographic/>

(Date Visited: 27 Jan. 2016) (Date Last Updated: 4 May 2012).

Geographic, National. ‘National geographic shows 30.9 Million worldwide audience via consolidated media report.’ National Geographic Society Press Room. [www document]

<http://press.nationalgeographic.com/2012/09/24/national-geographic-shows-30-9-million-worldwide-audience-via-consolidated-media-report/>

(Date Visited: 17 Feb. 2016) (Date Last Updated: 24 Sept. 2012).

Harman, Justine, Kate Storey, and Alex Rees.‘The crazy way teens are hiding their imperfections online: Finstagram.’ ELLE. [www document]

<http://www.elle.com/culture/tech/a29243/finstagram/>

(Date Visited: 12 Jan. 2016) (Date Last Updated: 9 July 2015).

Laurent, Olivier. ‘Creators of fake Instagram account showing a migrant’s journey speak out.’ TIME.com. [www document]

<http://time.com/3982506/immigrant-instagram-migrant-journey-abdou-diouf/>

(Date Visited: 12 Jan. 2016) (Date Last Updated: 3 Aug. 2015).

Pearson, Rebecca. ‘The Ugly Truth behind My Perfect Instagram Shots: A Model Confesses.’ The Telegraph. [www document]

<http://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/womens-life/11980031/Instagram-confession-The-ugly-truth-behind-my-perfect-model-shots.html>

(Date Visited: 12 Jan. 2016) (Date Last Updated: 9 Nov. 2015).

Ridley, Louise. ‘Migrant Instagrams his journey to Europe and the results are eye-opening.’ The Huffington Post UK. [www document]

<http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2015/08/02/migrant-instagram-journey-boat_n_7921536.html>

(Date Visited:12 Jan. 2016) (Date Last Updated: 3 Aug. 2015).

Geographic, National. ‘National Geographic Your Shot.’ National Geographic. [www document]

<http://yourshot.nationalgeographic.com/about/>

(Date Vivisted: 8 Jan. 2016).

![(fig. 3.1) Randy Olson. ‘Writer on Phone’.[8]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/53340653e4b0943ce189926c/1523802229836-XRBWFTIJ9PINER27STE3/Thesis_chpt3_001.jpg)

![(fig. 3.3) Ciril Jazbec. ‘Migrant Child.’[19]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/53340653e4b0943ce189926c/1523802651385-2MD1JSLNHX3EZEJUW8FF/Thesis_chpt3_003.jpg)

![(fig. 3.4) Image of the ‘migrant’ Diouf [25]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/53340653e4b0943ce189926c/1523802688991-LXMGO6WAXH3SIWNXMCWO/Thesis_chpt3_004.jpg)

![(fig. 2.2) Ami Vitale, ‘Protecting the last male white rhino’[29] shown on the National Geographic instagram account.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/53340653e4b0943ce189926c/1523801601321-HI2L3WUD48BNASZMDGW1/Thesis_chpt2_002.jpg)