This year I graduated from my Practice-led Masters by Research, which researched walking and visual representations of place. My thesis, titled “On Foot: Photography, Cultural Landscapes, and Ireland’s National Waymarked Trails” documents the theoretical research that went into my work, as well as the development of my artistic practice during this time. Below is the abstract and the start of the Introduction to this thesis.

Abstract

This thesis researches the evolution of walking and our interaction with place, discussing how experience can be shared, and the responsibility of image makers in their representations of place. The research is led by my walking practice, through which I have produced the first full documentation of Ireland’s National Waymarked Trails, a collection of 42 trails with a combined distance of 4,000km. From walking these trails I have considered how the Irish landscape has been affected by the picturesque aesthetic that has long been associated with it, and examined how the development of these trails is impacted by the perceived ideas of wild space in Ireland. Concerns are raised around the power of social media to influence representations of place and constructions of imagined geographies, which can lead to an abstraction between viewer and physical place. The theory of lifeworlds is used to analyse how contemporary photographic practice can include a sense of place and presence within a landscape, and the benefits of such work in grounding the photographic representations in a place.

fig. 0.1: Opening page to Footnotes: The National Waymarked Trails

Introduction

On the 17th April 2017 I handed back my apartment keys, shouldered a heavy backpack, and set out on a project to walk every National Waymarked Trail in Ireland.

The National Waymarked Trails of Ireland are a series of medium to long distance walking trails spread throughout the Republic of Ireland. The first of these trails was the Wicklow Way, which was established in 1982 by John B. Malone. It was quickly followed by the South Leinster Way and East Munster Way in 1984, as well as the Kerry Way and the Táin Way in 1985. At the time of writing, there are 42 open and walkable National Waymarked Trails across Ireland. (1)

The creation of these multi-day trails was inspired by the earlier development of the Ulster Way in Northern Ireland, as well as many of the famous long distance walking routes that can be found across Europe. The aim of these new walking routes was both to attract increasing numbers of international travelers, and also to create ways for local people to interact with their environment. (2)

Since the 1980s this trail network has developed into a body of over 40 trails, and 4,000km of walking. (3) These trails are typically defined as long-distance hiking trails, usually taking a minimum of 3 days to complete. They are designed to immerse the walker within the local landscape, whether crossing rural, urban, or suburban spaces.

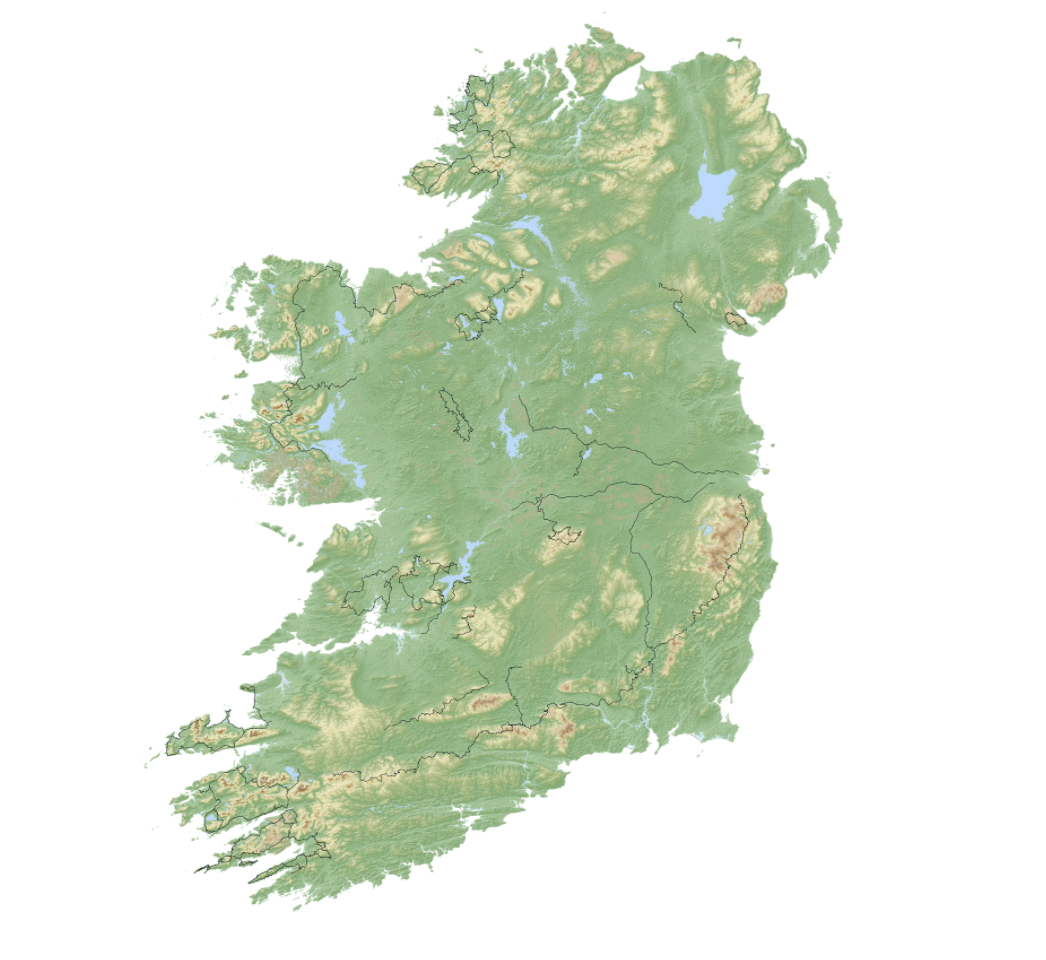

fig. 0.2: Overview Map of National Waymarked Trails, 2020 (4)

Over the course of 3 years, from 17th April 2017 to 28th July 2019, I walked all of the 42 National Waymarked Trails of Ireland with my partner Carl Lange. As far as I am aware, we are the first people to have accomplished this.

When we began walking in 2017, my recording, reflecting, and documenting of the process was purely a personal project. Through the opportunities that arose along the way, my walking developed into this Practice-led Masters by Research. In addition, during the years that this research has taken, my interests have expanded beyond looking at my own experiences, and into other people’s experience of nature and the outdoors, how we build and frame representations of place, and what our impact means for the future of our planet.

fig. 0.3: Tourists at Yosemite national park. Photograph: Gabrielle Cannon/The Guardian

In 2018 the Guardian published an article titled Crisis in our national parks: how tourists are loving nature to death. (5) In this piece a team of journalists discussed how Americans are flooding to their National Parks and landmarks simply to take a photo (of the landscape or themselves), which they can then post on social media, all towards building a specific visualisation of themselves that they want to share with the world. The article tells a cautionary tale: as visitor numbers go from a few thousand a year to five thousand per day, the human impact is unavoidable. In 2018 through the months of summer to autumn, The Guardian dispatched writers across the American West and National Parks to investigate how overcrowding was evolving on-site. “We found a brewing crisis: two mile-long “bison jams” in Yellowstone, fist-fights in parking lots at Glacier, a small Colorado town overrun by millions of visitors.” (6) As people queue to take their own variant of the same picture, each post further clashes this imagined geography that is being built within the social media landscape, against the physical geography that is impacted in the real world.

fig. 0.4: Crowds at Old Faithful in Yellowstone. Photograph: NPS/Neal Herbert

In the article, Simmonds writes that the National Parks of the US were once considered the “ultimate place to disconnect from the modern world” - however, today’s visitors “have fresh expectations – and in accommodating these new demands, some say parks are unwittingly driving the very behavior that’s spoiling them.” (7) Some consider the changes to the parks (such as the installation of camouflaged Wi-Fi towers) as a way of keeping parks ‘generationally relevant’, while others argue that the reason for visiting such places should be to experience the place without a screen interposing one’s view. As people flood to places that become ‘#instafamous’, the outdoor ethics organisation Leave No Trace has called upon people to avoid geo-tagging where they take their photos in a hope to lessen overcrowding and possibly the destruction of the wild space in question. While social media has made people more aware of how they construct their individual online identity and how they could be perceived within a space, we as a society have not taken the necessary step back to see our overall impact or image. Almost a year later in 2019, the Guardian published that roughly 96% of the U.S.A.’s National Parks are struggling with significant air quality issues, with the majority of the worst cases being the locations that had experienced extreme overcrowding in the year prior. (8)

fig. 0.5: Queue for the summit of Mount Everest. Nirmal Purja, 2019

However, the image of 2019 that highlights the disconnect between our cultural and visual framing of the outdoors, as well as our terrifying impacts and consumption of it, was taken at supposedly one of the most difficult places to reach on the planet.

Almost 66 years to the day from when Mount Everest was first climbed, Nepalese mountaineer Nirmal Purja photographed 100 people queuing to reach the summit. 2019 is now considered to have been one of the deadliest climbing seasons on Everest. While the good weather window that year was short, the problem wasn’t blizzards or avalanches, but too many people on the mountain. Veteran climbers and industry leaders have blamed these deaths on overpopulation, with particular focus on too many inexperienced climbers. (9) The above image sent shockwaves around the world as those who knew “nothing about mountaineering were shocked by this contradiction between the mountain’s reputation as a lonely and unattainable peak, and the banal reality of a rush-hour crush.” (10) That year saw a record number of permits to climb the mountain issued by the Nepalese government, and after the climbing season closed there were no signs that numbers would be restricted in the following year. As our consumption of nature felt like it was spiraling out of control, the world was brought to a standstill by the global Covid-19 pandemic.

When I started my research into walking I never expected a stage where I wouldn’t be able to go further than a couple of kilometers beyond my house. At the time of writing, March 2021, the world is one year into the Covid-19 global pandemic. In the past year Ireland has gone through a number of ‘lockdowns’, with movement restricted to specific distances from place of residence, or within regional counties. However, during these months there has been a marked increase in people ‘finding’ the outdoors. Mountaineering Ireland, (11) the recognised National Governing Body for mountaineering, hillwalking, rambling, and climbing, published an article by Helen Lawless in the Summer 2020 edition of The Irish Mountain Log, titled ‘Increase in physical activity seen during time of Covid-19 restrictions’. In the article Lawless writes how although many people cannot partake in their usual activities during Covid-19 restrictions, “research has shown that many people have ‘found’ the outdoors at this time.” (12) This research, conducted by Ipsos MRBI on behalf of Sport Ireland, (13) reports that “Irish adults walking at least once a week for recreation has increased throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, reaching 83% in May” 2020, and that “the percentage of people that are inactive is at its lowest ever (11%).” (14) In her article, Lawless questions how this new level of participation can be sustained into the future, with no clear answer in sight.

As the Access & Conservation Officer for Mountaineering Ireland, Helen Lawless has written about the impact of our increased recreational use of the outdoors in previous editions of The Irish Mountain Log. In Issue 132 (Winter 2019) Lawless published the article “Learning from Cuilcagh,” (15) a follow-on from a piece she wrote in 2017 about the same area, titled “Much to be Learned From Experience at Cuilcagh”. (16) Based on the titles I immediately knew that these articles would provide insight into the under researched topic of the cause and effect of an Irish location becoming famous on Instagram - I have seen this place hundreds of times depicted on the social media platform. Online this hike is known as ‘the stairway to heaven’, as the route follows a long boardwalk and staircase up to the summit of Cuilcagh Mountain (665m), the highest point in counties Cavan and Fermanagh. The focal point of all of the images that I have seen of the trail and surrounding area focus on the structure of the boardwalk, as the sun-bleached wood stands out starkly from the blanket bog landscape it twists through.

In the first article in 2017, Helen Lawless describes the background to the area: in the late 1990s all commercial peat farming ceased, and the bogland went through a series of conservation processes as a classified Special Area of Conservation (SAC) through the EU LIFE programme. Between 2003 and 2008 two walking trails were routed across this area, which encouraged more footfall and caused the trampling of a wide area as walkers tried to follow the trail without walking through other trampled, boggy areas. Early attempts at rectifying this problem only exacerbated the trampling of flora and destruction of the fragile ground, leading to a brief closure of the affected area. The council overseeing the development of the area decided to build a boardwalk (in this instance, boardwalk meaning a raised wooden walkway with handrails) to protect the area from further erosion.

In her article, Lawless writes that the announcement to build a boardwalk up to the summit of Cuilcagh mountain was met with concern from members of Mountaineering Ireland, who wrote to the Geopark that the bogland was part of, highlighting their issues. These issues included concern for “the visual impact of the boardwalk on the landscape, that the structure was out of proportion to the modest degree of erosion on Cuilcagh and that, through increased usage, it could exacerbate impacts on the summit plateau.” These concerns were, according to Lawless, ignored, as the legal category of the land didn’t require any further environmental assessment. At the end of this paragraph Lawless reiterates how “landscape and visual impact were not considered.”

The title of the next section of her article, The impact of social media, pinpoints just how far our lexicon and cultural landscape has changed in the past ten years. Lawless writes that in 2017, a video of this boardwalk became famous, “reaching 1.4 million views in three weeks,” which resulted in an estimated 3,500 people visiting Cuilcagh over the four day period of the Easter weekend that year, “greater than the total number of visitors for all of 2013.” From here Lawless draws our attention to the impact and stress this caused to the local residents and landowners, the extra security firm brought in to manage traffic, and the overworking of the Geopark staff. Lawless conducted a site visit 5 months after Cuilcagh’s rise to fame, finding that the erosion after the end of the boardwalk spanned an area wider than 50 metres, and continued across the ridgeline of the mountain for 1 kilometre. This high volume of tourism aged the area by 10 to 20 years of footfall within the space of these first few months.

Between September 2019 - March 2020 there had been a resurgence in trail assessment to make sure that the trails were continuing to conform to specific trail standards. Around then, every few months a trail might be closed for maintenance - or one that has been closed might be re-established. Since the Covid-19 pandemic started in March 2020 I personally know that work has been done on many of the closed trails. I expect the number of National Waymarked Trails to grow quite rapidly once the Pandemic as we know it to be has passed.

Setting New Directions: A Review Of National Waymarked Ways In Ireland. National Trails Office, and Irish Sports Council, 2010. p. 8.

https://www.irishtrails.ie/Sport_Ireland_Trails/Publications/Trail_Development/Setting_New_Directions.pdf. Accessed 7 Jan 2019.

Irish Trails. “Guide to National Waymarked Ways in Ireland.” Irish Trails, https://www.irishtrails.ie/Sport_Ireland_Trails/Trail_User_Advice/National_Waymarked_Ways/. Accessed 7 Jan. 2019.

An unfinished overview map of the National Waymarked Trails put together by Carl and myself when thinking about how to visualise the trails, 2020.

Simmonds, Charlotte, et al. “Crisis in Our National Parks: How Tourists Are Loving Nature to Death.” The Guardian, The Guardian, 20 Nov. 2018, www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/nov/20/national-parks-america-overcrowding-crisis-tourism-visitation-solutions. Accessed 1 Apr. 2019.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Canon, Gabrielle. “Fresh Mountain Smog? 96% of National Parks Have Hazardous Air Quality – Study.” The Guardian, 8 May 2019, www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/may/08/national-park-air-quality-hazardous-study.

Schultz, Kai, et al. “‘It Was Like a Zoo’: Death on an Unruly, Overcrowded Everest.” The New York Times, 26 May 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/05/26/world/asia/mount-everest-deaths.html.

Gentleman, Amelia. “‘Everyone Is in That Fine Line between Death and Life’: Inside Everest’s Deadliest Queue.” The Guardian, 6 June 2020, www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/06/everyone-is-in-that-fine-line-between-death-and-life-inside-everests-deadliest-queue.

Mountaineering Ireland is the representative body for walkers and climbers in Ireland. It is recognised as the National Governing Body for mountaineering, hillwalking, rambling, and climbing by both Sport Ireland and Sport Northern Ireland. Mountaineering Ireland is governed by a Board of Directors, elected by the membership. It has a professional staff team based at Irish Sport HQ, National Sports Campus, Blanchardstown in Dublin and at Tollymore Mountain Centre in County Down.

Mountaineering Ireland. “About Us | Mountaineering Ireland.” mountaineering.ie, mountaineering.ie/AboutUs/default.aspx. Accessed 25 Nov. 2020.

Lawless, Helen. “Increase in Physical Activity Seen during Time of Covid-19 Restrictions.” The Irish Mountain Log, vol. Summer 2020, no. 134, 2020, pp. 58–59.

Ipsos MRBI. “Impact of Covid-19 Restrictions on Sport and Recreational Walking.” Sport Ireland, May 2020.

Op. Cit. Lawless. 2020. p. 58.

Helen Lawless, “Learning from Cuilcagh,” The Irish Mountain Log, Winter 2019. Issue 132.

Helen Lawless, “Much to Be Learned From Experience at Cuilcagh,” 2017, http://www.mountaineering.ie/_files/2018125165027_89659124.pdf. Accessed 2 March 2020

This is the majority of the introduction to this thesis. I think this is as good a place to cut it as I am likely to think of - my reflections “how to climb a famous mountain” fits in pretty well contextually after this, as it’s about my personal experiences climbing Cuilcagh while being aware of all of the above. Having thought and written about this mountain for so long, I decided that to be able to draw my own conclusions fully I needed to visit it myself.

If you are interested in more of my research and artistic outcomes from this project, please get in touch!