Arts Council Agility Award 2022

This year I’ve received my first Arts Council of Ireland funding, through round one of their 2022 Agility Award. This grant was awarded on the premise of, as an emerging artist, I was looking to buy my own time to work on my practice and research how my practice can develop in new ways. Having graduated from my research masters last year, and having work featured in WALK! at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt earlier this year, I feel like I am at a pivotal point in my career.

I’m so happy to get to share that I’ve been given this funding - it’s these moments where I get to really believe in my practice, and I cannot wait to develop and share the projects that I’m working on for this year. I waited until more than a month to share the news of this award on social media (and two months for this blog post I think), as I didn’t fully believe it was actually happening. Thank you to the Arts Council of Ireland.

Remapping, Reimagining

In the projects tab of this website, you’ll now find Remapping, Reimagining.

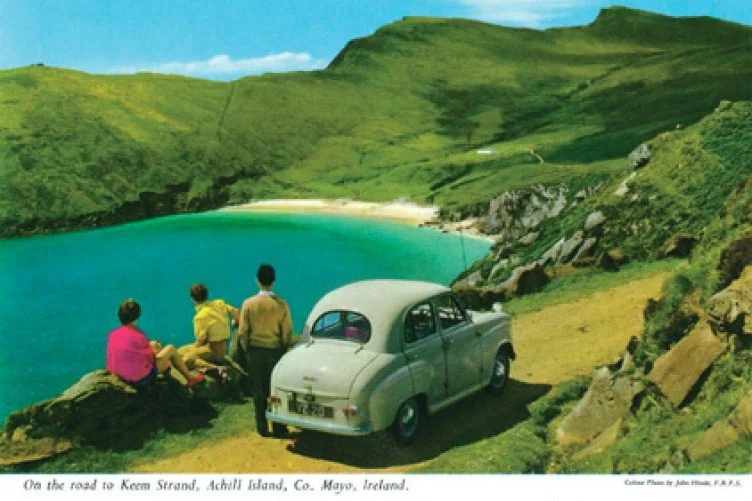

I’ve written two blog posts announcing this project (blog one and blog two), where I’m using open data to explore the different layers that make up the Irish landscape. I’m really excited to have started building the homepage for this project on my website. There are multiple layers to the Irish landscape that I want to explore, so from this page you’ll be able to find the research and writing I make about each different aspect.

To start off, I’ve written about Special Areas of Conservation (SAC’s) and what they protect in the Irish landscape. At the bottom of the SAC page you’ll also find free maps to download, each map featuring the SAC’s of each county of Ireland. Below is an extract from writing about SAC’s:

“Still laughing at myself, I make it past the reception, the gates, and maybe 200 meters down the now-empty commuter by-pass, before a sign catches my eye. That’s a lie - it’s the gravel on the other side of the road I notice first. It looked like the kind of gravel used for trails by county councils, and gave me the feeling that there might be a pedestrian way into the woods. When the sign did come into view, it’s the map that’s on it that actually pulls me across the road, excitement building at the possibility of an off road run.

The sign details loops do Bray head, and the trails that flow along its rising contours and cliffs. There’s always a lot of text on these boards, but my heart soars a little higher when it picks out the line that Bray Head is a Special Area of Conservation.”

I’ll also be featuring Ireland’s Special Protection Areas, Natural Heritage Areas, and Nature Reserves, as well as writing about the positive powers of Open Data and mapping in Ireland, so stay tuned for more updates soon!

This project is funded by the Open Data Engagement Fund, and will be featured in the Walk21 Conference in Dublin, September 2022.